I have been revising the programme synopsis for our forthcoming production of Figaro, which has got me thinking hard about the purpose of synopsis in general. To recap, a synposis is a brief plot description. Here is one about the movie Her:

A sensitive and soulful man earns a living by writing personal letters for other people. Left heartbroken after his marriage ends, Theodore (Joaquin Phoenix) becomes fascinated with a new operating system which reportedly develops into an intuitive and unique entity in its own right. He starts the program and meets “Samantha” (Scarlett Johansson), whose bright voice reveals a sensitive, playful personality. Though “friends” initially, the relationship soon deepens into love.

This example, plucked at random, exhibits all the characteristics of what I will call synopsese. I think it’s pretty awful writing, personally. Paired adjectives (“sensitive and soulful”, “sensitive, playful”, “intuitive and unique”), odd word choice (“reportedly”?) and cliché (“deepens into love”) combine to kill any desire I may have to see this movie. What the paragraph does not do, for me at least, is to impart any of the flavour of what I know to be a charming, subtle and melancholic film by one of my favourite directors.

So why do synopses exist? In the literary world, they are used by writers to pitch a story to editors and publishers without them having to read (or sometimes even to write!) the whole work. In film, they serve similarly as a pitch to potential viewers, to persuade them that this a movie they will want to see.

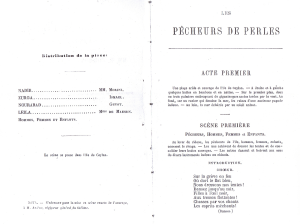

But in opera, I very much doubt that a synposis has ever succeeded in persuading a patron to attend one opera and not another. We love operas because the stories they tell are heightened by music, and I can’t think of an opera with a fantastic plot and appalling music which has stayed in the repertoire. So why do synposes appear everywhere? I can’t discover when they took hold in programme booklets, but I do know that throughout the nineteenth century and into the twentieth, patrons would buy the libretto, and read it as a piece of theatre writing. Here is the first page of the livret for The Pearl Fishers, which came out around the time of the 1863 premiere:

This presents a (pretty terrible) libretto as a piece of literature. It gives us the cast and character list, and gets straight into scenic and textual detail. Audiences would take the time to prepare for their evening in the theatre by reading these libretti.

When I prepare to conduct an opera now, I always start with the libretto before I work on the score. It used to be the other way around, and in my early years I would barely think about the words. Now I am much more focused on storytelling, and have realised that if I don’t think about how to tell the story through the music in my conducting, the performance will be thinner and less engaged. There’s a wonderful anecdote about the great singing actor Andrew Shore coming offstage at the London Coliseum, hitting himself on his forehead and muttering repeatedly to himself “tell the story. Tell the story. Tell the story”.

This leaves the issue of synopses unsolved. In Quaintaince Eaton’s words,

To write a short synopsis of an opera and keep it clear and sensible is very difficult. To attain to any literary distinction in such writing is virtually impossible.

(Opera Production II: A Handbook [1974])

Literary distinction aside, I believe that synopsis-writing in opera has grown from the following anxieties:

- The opera is in a foreign language and so the words will be incomprehensible

- The opera is sung and so the words will be incomprehensible

- The opera has a ridiculous plot and so the action will be incomprehensible

- The singers are terrible actors and so the action will be incomprehensible

- Opera is an alienating, anti-naturalistic experience and so the audience needs all the help it can get to engage with the stage

Actually, all of these anxieties are about comprehensibility. Western audiences can (and do) go to Nōh theatre in Japan, despite understanding neither Japanese nor the traditions of the Nōh theatre. In London there is a taste for Shakespeare productions in Serbian, Hindi or Bantu. But these are refined, metropolitan tastes. Opera is from our own Western culture, sung in languages we accept as European, in a traditional Western theatrical tradition. If we are not telling the story effectively to our audiences, that is our fault – and a synposis not only fails to solve that, for many it is an actual turn-off. Its bizarre language and sheer incomprehensibility can reinforce some patrons in their conviction that opera is absurd, inaccessible and alien.

Opera surtitles, which we use at West Australian Opera, are a modern solution to the telling of text in real time. They serve as an accelerated form of libretto-reading in conjunction with the performance. Although there are issues with some aspects of surtitles (legibility, distraction and precise timing for comedy), they are an accepted audience tool. They don’t permit the kind of preparation that libretto booklets did in the past, however, and I would encourage interested patrons to read widely before coming to the theatre.

My wrestling with the programme synopsis for Figaro is not yet resolved, so you can wait until June to find out how it plays out! Let’s have a little competition – send in your own Figaro synopsis (with no synopsese), and I will credit and publish the best one. That will get me out of a hole!

I will return to the matter of naturalism in opera in a future post, and I know I promised to talk about the art of season planning. I’ll come back to that as well.

Until next time.